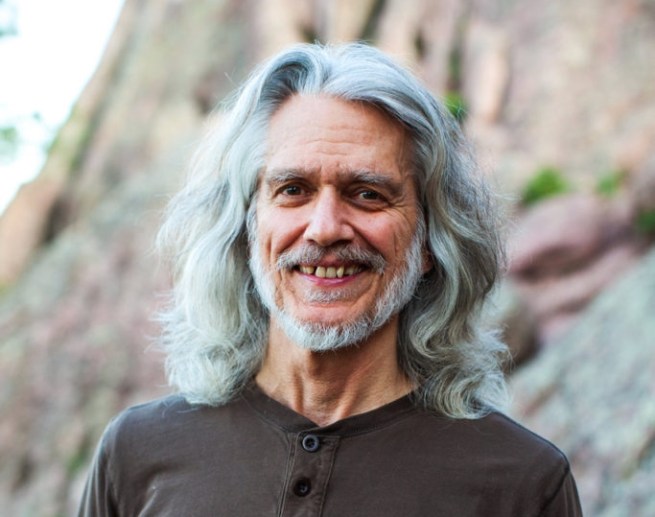

John Whitney Steele, author of The Stones Keep Watch, in conversation with Randal A. Burd, Jr.

EXTRA! Read a review of The Stones Keep Watch.

Randal A. Burd: I was honored to have the opportunity to interview the poet, John Whitney Steele, author of recently released The Stones Keep Watch (Kelsay Press, 2021) to discuss his work. I was drawn to his work because of my love of poetry that demonstrates humble introspection as well as astute observation. Steele’s work does both exquisitely. When asked to identify his muse, he is quick to name his spiritual practice of yoga and Zen and his love of nature as his primary inspirations.

Burd:. Where does The Stones Keep Watch fall in your poetry career?

John Whitney Steele: I started writing poems in high school and took a poetry writing class during my first year of college. Then I pretty much gave up on writing for the next four decades as I pursued my career as a clinical psychologist, mindfulness instructor, and yoga teacher. It wasn’t until 2015, when I enrolled in the MFA Creative Writing program at Western Colorado University, that I began writing in earnest. A year later, when Blue Unicorn was the first journal to accept one of my poems and the editor later nominated it for a Pushcart Prize, my poetry career got a boost. This year, Kelsay Books’ publication of my first collection, The Stones Keep Watch, catapulted me into what I have found to be the most challenging aspect of my role as a poet: building a website, promoting myself on social media, setting up a Zoom reading; in short, going public.

BURD: I had read that you came to writing poetry later in life. What first inspired you to write poems?

STEELE: I’m not sure what first inspired me, but as an extremely shy, introverted child, I was so socially withdrawn that the natural world and books were my closest companions. I was an avid reader of fiction and lapped up the poetry we studied at school and the bible stories I was exposed to at Sunday school.

During high school I took up guitar, sang folk songs and wrote a few poems. My social isolation may have contributed to my need to express myself through music and poetry. The feedback I got from my creative writing professor, the poet, Frank Davey, during my first year in college, gave me a sense that I had some talent.

Though I thought about pursuing creative writing and supporting myself as an English teacher, I doubted my ability to flourish in either field and decided instead to major in psychology. During grad school, my involvement with a Sufi community awakened my interest in Rumi’s poetry. By the time I had turned 40, I had left the Sufi path and become deeply involved in yoga and Zen. This led me to start reading Japanese haiku and Tang dynasty poets.

When I started offering meditation classes, I read some of Mary Oliver’s poetry, which was relevant to what I was teaching. My long-neglected urge to write kept resurfacing and I experimented with haiku. When I turned 60 and started to think seriously about retirement, I was haunted by Mary Oliver’s question: “What is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?”

I had long regretted neglecting poetry. It was clear to me that I wanted to give it another try. I started by auditing an undergraduate creative writing course at CU Boulder. Though I started writing poems again and received some good feedback, the workshop format of the class provided no instruction in craft.

Searching online I found the MFA program at Western Colorado University, one of the few programs that focused on writing formal verse. Although the tuition fees gave me pause, I decided it was now or never, and took the plunge. And that has made all the difference. [NB: line from “The Road Not Taken,” Robert Frost.] I wasn’t thinking about publishing. I simply wanted to learn how to write, but one thing leads to another and here I am.

BURD: Who or what is your muse now? I noticed that climate change is a common theme throughout your book, along with some political commentary. Is that what continues to drive you?

STEELE: My inspiration comes primarily from two sources: my love of nature and my spiritual practice, rooted in yoga and Zen. I’d rather sing songs of praise than write about climate change and politics. However, my angst and grief in relation to our inadequate response to the climate crisis has been driving me.

I love the natural world and my instinct is to preserve it. But the population explosion, the demand for constant economic growth, and the catastrophic destruction of the ecosystems and habitats we and other species depend upon is taking us in the opposite direction. And so, I felt compelled to write about the climate crisis and the politics of denial. Now that The Stones Keep Watch is behind me, I’d like to move on to other themes.

BURD: Do you write your poems to facilitate change outside (in the world) or change inside (in the reader)? Do you personally find writing poetry to be a cathartic process?

STEELE: I write because I am fascinated by words, the incantatory power of repetition, rhythm, rhyme, assonance, alliteration and so on. As much as I would like my words to facilitate change in the hearts of readers and to see that change ripple out into the world, it is certainly not in my mind when writing poetry. Writing is cathartic for me. It makes me more alert and responsive to myself and the world, gives me the ability to articulate my feelings on the deepest level, and as Frost so famously said, a well-wrought poem ends “in a momentary stay against confusion.”

BURD: Who are some of your favorite poets? Which poets have influenced your writing?

STEELE: In addition to poets I have already referred to, my short list of favorites must include the likes of Shakespeare, Milton, Blake, Wordsworth, Keats, Shelley, Coleridge, Hopkins, Dickinson, Whitman, Millay, Yeats, Frost, Jeffers, Larkin, Heaney, Rilke, and Merwin, not to mention the countless contemporary poets whose work I admire.

As for the poets who have influenced my writing, it’s hard to say. Some have told me my poems resemble those of Jeffers. Others have mentioned Keats, Wordsworth, Frost, Snyder and Charles Wright. But it seems to me that the body of literature contained in The King James Bible has been my biggest influence.

BURD: I notice your style in this collection is a mixture of classical and contemporary. It is often said that traditional forms, rhyme, and meter are unfairly shunned in today’s literary circles. Have you had difficulty placing some of your more traditional pieces in poetry magazines?

STEELE: No, not really. Though it has required a lot of research to find publications that welcome formal poetry, plus a thick skin and dogged determination in the face of multiple ‘no-thank-you’ responses from editors, I have managed to find good homes for most of the poems I have sent out.

BURD: What is your process for writing poems? Is it deliberate and scheduled or as the inspiration comes?

STEELE: I don’t schedule writing time. I write as the inspiration comes. However, there is definitely something deliberate about my process. I make writing my top priority, set aside plenty of unstructured time for it, read the work of other poets and follow up on every lead that my muse offers.

Inspiration is most likely to come while walking in nature, practicing yoga, doing zazen, or upon waking from sleep. Once I get started on a poem, the muse grabs me by the collar and won’t me let me go. I wrestle with it day and night. New ideas bubble up in my sleep or while out walking or practicing yoga or doing the dishes, and I jot down notes or go straight to my laptop to revise whatever poem I am working on.

I find my participation in weekly poetry feedback sessions with a group of poet friends is a strong motivator. I do my best to bring a new or revised poem to every meeting. If a week or more goes by without starting a new poem or continuing to finesse an older one, I worry that my muse has abandoned me or I have abandoned her. I start to doubt myself, wonder if I have somehow lost the knack of writing and think that I’ll never experience the joy of writing another poem. Almost every poet I talk to encounters similar cycles of monsoon and drought.

BURD: How long did it take for this book to come together?

STEELE: I wrote the poems over a period of five years, along with many other poems that don’t fit into the theme of this book. I pulled the poems together over the course of a couple of months and then sent my manuscript to a few publishers. A couple of months later, an acceptance email from Kelsay Books showed up in my inbox.

BURD: I notice your back cover has blurbs from poet laureates of three different states. Were these blurbs hard to obtain? What was the process?

STEELE: I wanted to ask Joanna Macy, an environmental activist, author of twelve books, and scholar of Buddhism, general systems theory, and deep ecology, but I had no personal connection with her. However, I remembered that a friend who teaches environmental leadership at Naropa University had helped organize a workshop Macy had given. When I contacted my friend, she told me that at age 92, with declining health, Macy is saving her energy for the work she values most and is no longer accepting requests for book reviews or blurbs.

Then, I thought of Jane Hirshfield, a poet who writes at the intersection between poetry, the sciences, and the ecological crisis, but I couldn’t find any way of contacting her. So, I reached out to three prominent poets I have met and whose work I admire. Fortunately, all three said yes, and sent wonderful blurbs that gave me new perspectives on what I had written.

BURD: The Stones Keep Watch is published. The reviews are trickling in. What is next for you?

STEELE: My full-length book, Shiva’s Dance—a collection of sonnets about yoga, which more closely resembles the songs of praise I want to be writing—was accepted by Kelsay Books last summer and scheduled for publication in the spring of 2022. After having had no nibbles from the contests and publishers I had been offering the manuscript to for over two years, I was quite relieved to get the good news from Karen Kelsay.

I am currently working on memorizing as many of the sonnets as I can in preparation for a promotional video in which I will be performing yoga poses as I recite poems from the collection. I will soon be working on sending the manuscript out to book award contests and reviewers and setting up reading events.

After being distracted from creative writing over the past couple of months by my efforts to promote my chapbook, I am looking forward to setting aside more unstructured time in the hopes that I will be inspired to write new poems. As for what I will write, I have no idea. My muse has a mind of its own!

John Whitney Steele is a psychologist, yoga teacher, and assistant editor of Think: A Journal of Poetry, Fiction and Essays. He is a graduate of the MFA Poetry Program at Western Colorado University. His poetry and book reviews have appeared in numerous print and online journals. Born in Toronto and raised among the pines and silver birches of Foot’s Bay, Ontario, John now lives in Boulder, Colorado where he often encounters his muse wandering in the mountains. John can be found at johnwhitneysteelepoet.com.

Randal A. Burd, Jr. is an educator and the Editor-in-Chief of the online literary magazine, Sparks of Calliope. His poetry has received multiple awards and has been featured in numerous literary journals, both online and in print. Randal’s 2nd poetry book, Memoirs of a Witness Tree, is now available from Kelsay Books and on Amazon.

Risa Denenberg is the curator at The Poetry Cafe.