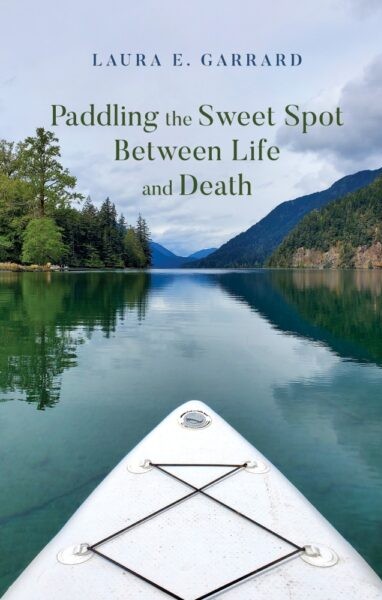

Lauren Davis in conversation with Laura E. Garrard,

author of Paddling the Sweet Spot Between Life and Death,

Finishing Line Press, 2026

Lauren Davis: Congratulations on the publication of your debut chapbook Paddling the Sweet Spot Between Life and Death (Finishing Line Press, 2026), which the poet Tess Gallagher has called “a true teaching of how to live daily on the shifting edge of our own mortality and that of those we love.” Truly, this is a book that looks impermanence straight on. Can you tell us a little bit about how this book came to be?

Laura E. Garrard: This book is an offspring of a full-length poetry memoir about my initial cancer experience (2020-23) interspersed with nature-focused poems. Poems appear in this book that were not part of the full-length narrative, some of them having been published. A number received repeated comments about how readers related to them, regardless if they had cancer or not. The book begins with the title poem “Paddling the Sweet Spot”—which addresses the fleeting balance of flowing smoothly in life’s waters (“the sweet spot not easy to maintain”) and, I think, the crux of a cancer experience (the balance of being responsible and accepting within the medical realm but also remaining hopeful and true to oneself). From here, the poems proceed according to my emotional progression.

Readers may notice how my thoughts about my own death evolve from shock, to grief, and to acceptance of it as a natural cycle alongside living, playing, and observing. The reader travels with the speaker through this arc of the book and her observations of and participation in nature. Living in the present, sharing grief with one another, and loving, are the speaker’s priorities as a living person who is also dying. We are all simultaneously living and dying, no matter how quickly or slowly death comes. Why fear what is inevitable and spend precious energy on worry? Notice how the barn swallows play as the sun sets, how feeding and nurturing the next generations consume them. Notice how salmon give themselves to death even as they lay and fertilize eggs. Are they focused on birth or death? Most likely birth.

Living in the present, sharing grief with one another, and loving, are the speaker’s priorities as a living person who is also dying.

LD: In your poem “Sailing in the Sunshine,” which explores the “sweet spot of flow called letting go” between will and acceptance, you mention “the peaceful present.” Could you speak to your process of letting go when writing poetry and publishing a book, and how the present moment informed that process?

LEG: Interesting questions. The incentives to submit poems for publication and to present a chapbook are two-fold. I have always desired to be published and share my writing, and I want to provide a voice on behalf of those who face similar challenges. These poems have been instrumental as I learned from indelible moments. I believe others may feel validated.

Launching my work into the public realm is a type of letting go. I had to let go of pride, self-protection, and some of my privacy. I thought long about how I might feel reading these poems to others in person and how others may respond. I tested the waters locally as a featured author for Olympic Peninsula Authors’ Open Mic and determined I could bring these messages without causing myself mental and emotional harm or breaking down while reading them. I found myself resilient and others very receptive. The poems aren’t all tearjerkers, mind you. Some are very uplifting and joyful, strong and irreverent. But I lived through these moments, and they challenged me.

Becoming published is service both to myself (sharing experiences and achieving a dream) and to others (offering my voice and circumstances for a shared identity). Opening myself up to rejection in the submission process requires present-mindedness. The focus needs to be on what comes, not on what doesn’t come. This process of patience isn’t easy, especially with such heartfelt material. Not taking things personally is a form of letting go. This is a lesson I aim to learn.

LD: Where did you find inspiration while compiling these poems? Did you turn to any specific authors or books?

LEG: Inspiration spilled from my cancer experience and the weight of a possible decreased lifespan. Nature and its beings speak to me as well, tell me to become present and turn off churning thoughts. I am living in the moment when I cast my gaze upward, climb into a tree, and seek the sublime, like the joyful antics of dolphins and barn swallows at play. I awoke in the middle of the night composing the poem about the life of a rock, “A Life Worth Remembering.” I wrote the entire poem within my mind before rising from bed and composing it again on the computer. I wrote “The Only Else There Is, the Breath” after crying on my shins on the cold brick, begging healing from God. When the tears dried, I came off the floor and began doing Qi Gong. This was a survival instinct to move past a moment of despair. I have lived these moments, and they seemed important to record.

I have lived these moments, and they seemed important to record.

The poetry muse lives within the poet artist, and I don’t always know how a poem came to me, just that it’s here—a thought, a recognition, a personal revelation. Poems seem to have their own lives that poets capture and hone. Poets don’t create in a vacuum, however. Certainly, my writing groups influenced my work, especially an ongoing workshop with poet Gary Copeland Lilley. This chapbook’s poems are flavored through my mentors from Centrum workshops as well. I have studied with Holly J. Hughes, Tess Gallagher, Alice Derry, Matthew Olzmann, CMarie Fuhrman, Claudia Castro Luna, and others. Their classroom reading selections influenced my work, no doubt, but I haven’t emulated a particular poet or style.

The title, “Homage to My Radiated Hip,” shouts out to Lucille Clifton, whose concise work and hard-hitting subjects I admire. Ultimately, though, I believe these poems are written in my unique voice, an upwelling from personal fear, loss, and relief.

LD: If you could leave your reader with one final thought or word, what would it be?

LEG: I hope that readers reduce their fear in relation to dying and become inspired to stand against ableism, or discrimination against those with illness or disabilities. I did not share my work to receive responses of “how sad” but for potentially “how inspiring.” I’ve already been through these moments. I do not dwell on my death date, an unknown to all of us. I am not interested in sympathy. I am interested in others receiving validation through reading my collection, and to further understanding of the emotions that come with being diagnosed with a terminal or chronic disease and dealing with the stigmas of having cancer.

I did not share my work to receive responses of “how sad” but for potentially “how inspiring.”

When we share openly, we gain strength in our experiences rather than feeling alone in them. I would encourage readers to embrace trust within the unknown as best they can, and let that steer them rather than fear. This is not an aim toward perfection but a returning to, again and again. My wake-up call may serve others. When I reread this collection and my full-length book, I am reminded of the gift of raw uncertainty, the lack of security, which drives the ability to live in the present through heightened observation.

Laura E. Garrard is a CranioSacral Therapist on the Olympic Peninsula. Her poetry has appeared in journals such as Bellevue Literary Review, Amethyst, The Madrona Project, Silver Birch, and TulipTree Review. Her chapbook, Paddling the Sweet Spot Between Life and Death, is available through Finishing Line Press. Winner of the Merit Prize for the 2024 Stories That Need to be Told Contest with TulipTree Publishing, she has also been a finalist for the John and Eileen Allman Prize for Poetry. She writes a series, Poetry That Fits, on Penn Medicine’s OncoLink.org, and she holds a Master’s Degree in Journalism. Learn more at LauraEGarrard.com.

Lauren Davis is the author of The Nothing (YesYes Books), Home Beneath the Church (Fernwood Press), When I Drowned, and the chapbooks Each Wild Thing’s Consent, The Missing Ones, and Sivvy. She holds an MFA from the Bennington College Writing Seminars.

Risa Denenberg is the curator at The Poetry Cafe Online.