The Optimist Shelters in Place, by Kimberly Ann Priest

Published by Small Harbor Publishing, Harbor Editions, 2022

Review by Maria McLeod

“The significance of bearing witness“

The Optimist Shelters in Place, a poetry chapbook by Kimberly Ann Priest, is an account of survival during a plague. The mundanity of daily routine provides a setting for existential angst which appears to the reader as universally familiar. Published during the ongoing Coronavirus pandemic, Priest’s chapbook chronicles the early days of isolation as if intent on creating a public and personal record of our adaption to a previously unfathomable circumstance.

The reader can imagine a future historian turning to Priest’s writing to learn the scope of the pandemic’s impact, as it reads as a reliable narrative, an unembellished account. Priest records this new and unwelcome homebound existence—beginning in March of 2020 as a quarantine of unknown duration—in order to signal her intent to the reader through the construction of 24 themed poems, all written from third person point of view, each title beginning with “The optimist” followed by an action taken by the optimist (or someone in her life). For example:

“The Optimist Scrambles Four Eggs for Breakfast”

“The Optimist Cuts a New Plant”

“The Optimist Takes a Personality Test”

Opening with a scene of a woman (the “optimist”) talking to her plants, Priest places us in that moment—pre-vaccine —when it seemed the only way to survive an isolated present was to hope for an “inhabited future”:

The plants feel it too.

She tells them to think about new sills to adorn

in some inhabited future,

not to imagine this will be their final resting place. She tells them

what her daughter told her before leaving was deemed essential:

this is all temporal.

Although confronting and combating loneliness rides the surface of these poems, the more salient theme expressed is the significance of bearing witness. Evidence is presented to the reader in the form of the book’s dedication, “for the spider,” a reference to the tenth poem in the collection, “The Optimist Leaves a Dead Spider Dead on the Carpet.” Here, the spider serves as a metaphor for our existence as measured by our significance, or insignificance, to others:

From underneath her coffee table a lone spider

plans a route of escape.

Quarantine is difficult for all sorts of creatures.

At dusk, when shadows brush the carpet a semi-cloudy grey,

he leaps out from under swimming over its follicles,

but not fast enough.

His smushed dot remains on the carpet for over three days.

The choice of third person point-of-view provides readers with both a comfortable perch and an active part. If one is to transcend loneliness and the resulting feelings of insignificance, one’s existence requires recognition. The reader takes the witness chair.

Amidst the details of daily life—the grocery shopping, the scrolling through Facebook, the phone calls, the tending to (or ignoring) domestic chores—the pandemic facts and stats are placed throughout the book. These are actual news items. Their inclusion provides both a reality check and a foil to the “optimist” whose survival tactics include moments of personal indulgence that allow a form of escape: a glass of expensive wine, a walk on the beach, a hand in the sand.

In North Carolina the Death Toll is 507.

But no one is talking much about North Carolina,

and she wonders what it’s like not to be talked about so much.

Again, it’s being talked about, being recognized, that Priest asks her readers to consider; this comes not as a directive, but an emphasized remark. It’s as if she’s raising her eyebrows at the end of sentence, inserting a pregnant pause. Descriptions of being seen represent moments that serve to buoy the speaker: the interested glance of a grocery store worker; her daughter’s brief but pleasant visit. But there is also a concern expressed over the opposite, to be unseen, unrecognized:

Not essential, no one has called her in weeks;

she’d rather die somewhere else than right here, alone.

Perhaps the most pointed lines in the collection come from the poem, “The Optimist Remembers What is Needed to Feel Essential.” Here the reader learns that a contributing factor to the optimist’s isolation is divorce, the dynamics of which are indicted by the following two lines, “The last thing her husband said to her is no one will want you / after this. Maybe he was right.” It is the words the poet sets in italics, representing the now ex-husband’s stark remark, that lift off the page like a slap, followed not by a refutation but a deflated concession by an omniscient narrator, “Maybe he was right.” These lines double the impact of the loneliness and isolation presented by this collection, an existential crisis expressed in the need to be seen, heard, loved and recognized in order to feel human and present in this world—needs that were challenged during the pandemic.

It makes sense, then, that the last poem, “The Optimist Sleeps Through the Night,” is about survival, focusing on the act of breathing as recognition of one’s existence. The poem’s subject is someone apparently unknown to the “optimist,” someone ailing and hospitalized. The speaker imagines the patient’s revival after what we can only assume has been a harrowing hospital stay, a near-death experience. In doing so, she uses her omniscience as a means of harnessing the power of positive thinking, as if her ability to see him helps bring him to life. Here Priest ends, as an optimist would, on a positive note:

… Somewhere/a fever has broken

Somewhere a young man wakes

to discover the sounds of his own breathing—how much like love it is.

An exhale of carbon monoxide

and hope.

Kimberly Ann Priest is the author of Slaughter the One Bird, the American Best Book Awards finalist. She is also the author of four chapbooks: The Optimist Shelters in Place, Parrot Flower, Still Life and White Goat, Black Sheep. She is winner of the Heartland Poetry Prize 2019 from New American Press. She teaches writing as an assistant professor for Michigan State University. She also serves as associate poetry editor for the Nimrod International Journal of Prose and Poetry.

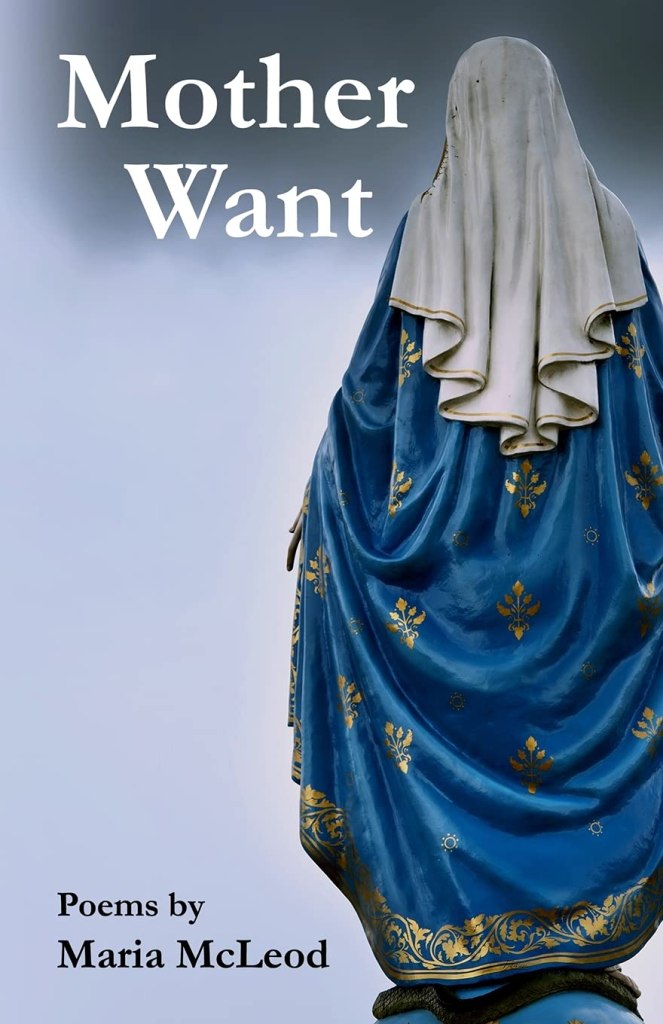

Maria McLeod is the author of two poetry chapbooks, Mother Want and Skin. Hair. Bones. She’s won the WaterSedge Chapbook Contest, Indiana Review Poetry Prize and the Robert J. DeMott Short Prose Prize. She works as a professor of journalism for Western Washington University.

Risa Denenberg is the curator of The Poetry Cafe Online.