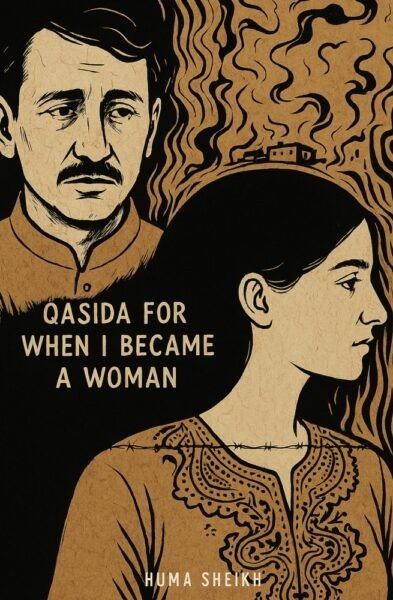

Qasida for When I Became a Woman, by Huma Sheikh

Published by Finishing Line Press, 2026

Reviewed by Kubra Nazir

Our Homeland, Kashmir, has a peculiarity about silences. Tales and tragedies rarely culminate there; they return in memories, in flashbacks, in whispers. Among those screaming silences, I once heard the story that lies at the heart of Huma Sheikh’s life, the loss of her father, the tragedy that shaped her becoming. While I was reading Qasida for When I Became a Woman, it felt like stepping into a realm where long-kept silences resurrected as an elegy of endurance. The poems, like a phoenix, emerge from the crevices of memory, transforming grief into poetry and memory into resistance.

As a fellow Kashmiri, I understood how she carried that ache all these years— an ache of a homeland that teaches its daughters to speak through absence. She doesn’t mourn alone, rather she crafts word by word what the past tried to blanket. Qasida, a classical Arabic poetic form of praise or elegy, has been turned into an instrument of invocation here, an unburdening where womanhood emerges through memory and silence.

The title of the poetry collection suggests a transformation of what it means to be a woman, and a reclamation against the silencing of women’s voices. It shows what it truly means to inherit both language and silence.

Each line is layered with so much depth and feels like a threshold between the personal and the collective. It reminded me of how writing poetry becomes the very act of witness not only of suffering but of survival. In the poem, “For Kashmiris, war an everyday meal,” she writes,

How to rebuild

a sense of refuge when hope beans spill and death blooms

for the kin of the slain, memories of dear ones, the

endless crackle of a flesh storm?

In Sheikh’s hands, the Qasida becomes an instrument of dialogue between what was taken and what refuses to be silenced. Throughout the poems, she goes back and forth to that memory of her father that changed the entire course of her life. She remembers her father, not as a figure lost to time but as a presence that still inhabits her silences. Her father, a renowned singer of Kashmir, somehow lives in the cadence of her lines as she pays tribute to him and his memories, echoing his songs through the collection like refrains. In the poem, “Qasida for a woman on a train,” she writes,

A Brooklyn subway’s screech like Father’s last Ghazal

Kam yaar sapidh khwaab jammed into a cassette

recorder. …

Throughout the poetry collection, the past peeks into the present, drifting between temporal planes; moments of childhood arise in her present voice, showing how a woman’s silence is the loudest cry. The inheritance of silence is portrayed as imagery that fuses the domestic with the divine. Sheikh’s silence becomes a prayer; her body becomes a landscape of remembrance. Each line is an instrument of reclamation, showing the way for women to respond. Every word feels earned and every pause deliberate.

As I read through the poems, I could sense a quiet ache in the depths of each line. Her poems are a reminder of how survival sometimes lives quietly in long-kept silences. These poems are more of a collective elegy, a shared act of remembrance, where one woman is speaking on behalf of a those who are still in the journey to find a voice.

In this quiet act of gathering sorrows of many, the solitary transforms into a wound others can feel too. A gathering of voices of those who have endured, remembered, and kept speaking even when the world turned away.

Huma Sheikh is an author, poet, and scholar. Drawing from her Kashmiri roots, her work blends personal narrative with political history. Her writing has appeared in Kenyon Review, The Journal, Consequence Magazine, Cincinnati Review, and Prism International, among others. A finalist for multiple literary prizes, she holds a PhD in English (Creative Nonfiction) and teaches writing at George Mason University. Her poetry chapbook, Qasida for When I Became a Woman, was a finalist for the New Women’s Voices Chapbook Competition (Finishing Line Press) and shortlisted for the Own Voices Chapbook Prize by Radix Media.

Kubra Nazir, a seeker of stories, has completed her Bachelor’s and Master’s in English Language and Literature from Kashmir University. Her work across corporate and teaching spaces has enriched the clarity with which she reads and writes. She has taught English Literature at the postgraduate level and contributed to research and editorial projects. In addition, leading a team of creative writers, gave her the fulfilling experience of guiding a diverse group of writers from across the world. Rooted in Kashmir and deeply in love with writing, she dreams of crafting a book someday—one that carries her voice, her memories, and the stories that have shaped her.

Risa Denenberg is the curator at The Poetry Cafe Online.