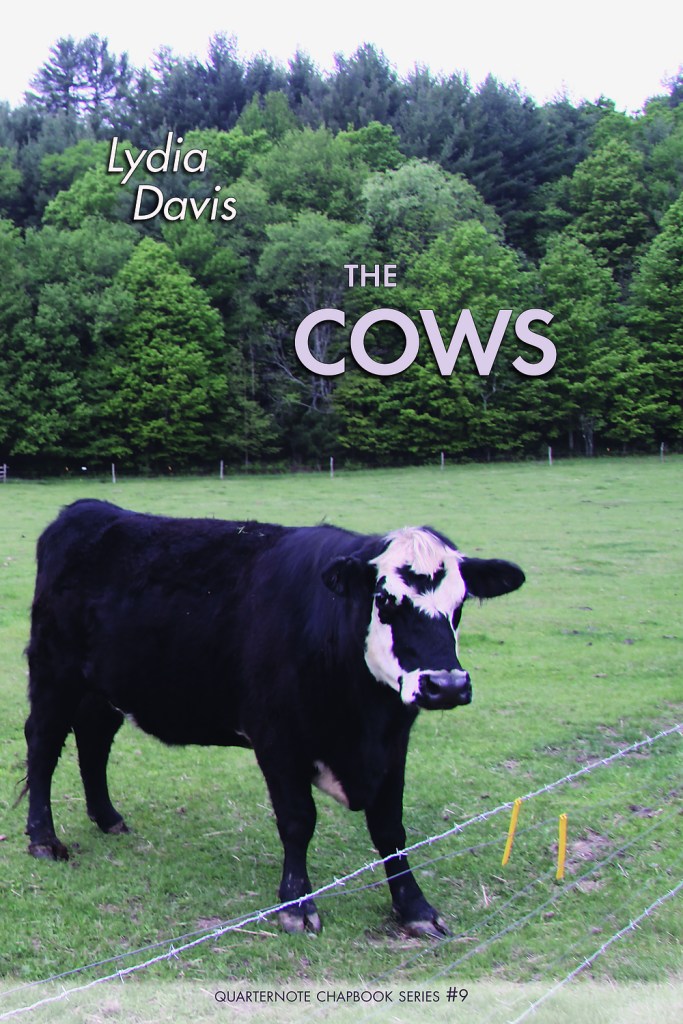

The Cows, by Lydia Davis

Review by S.M. Tsai

One may be jealous of another being licked: she thrusts her head under the outstretched neck of the one licking, and butts upward till the licking stops.

Lydia Davis’s The Cows (Sarabande Books, 2011) brought me back to every instance in which I stared at my childhood pets wondering “what are they thinking about?” Anyone who has spent prolonged time with animals will get a familiar feeling when they read this chapbook: the desire to decipher an animal’s intentions in the absence of a common language (while sometimes projecting personalities onto them). How many of us have monologued in tandem with an animal’s mysterious actions, or held mock conversations with said creature as they went about their business?

This chapbook is not a collection of individual poems, nor does it feel exactly like a standard short story. I can only describe it as a 38-page poetic observation of bovine life—one that is interspersed with photos, taken by the author during her year-long observations.

Davis has written other stories about animals, including cats, mice, and fish. Upon comparing these stories, we see that each type of animal can provide a different viewing experience to the human voyeur, due to their varied habits and needs.

In The Cows the theme of stillness is pervasive. The various incarnations of this stillness are portrayed throughout, for example:

How often they stand still and slowly look around as though they have never been here before,

And,

[. . .] they are so still, and their legs so thin, in comparison to their bodies, that when they stand sideways to us, sometimes their legs seem like prongs, and they seem stuck to the earth.

In a lifestyle marked by stillness, what are the things that bring action to a cow’s daily routine?

As Davis demonstrates, their stillness is set against a changing landscape of seasons (white snow to green grass), disturbance of other animals (flocks of birds, snowball-throwing boys, gaping writers), and the birth of calves. Ever-analytical, Davis also itemizes their forms of play:

[. . .] head butting; mounting, either at the back or at the front; trotting away by yourself; trotting away together; going off bucking and prancing by yourself [. . .]

The Cows thus depicts an ambling, relatively tranquil (but quietly humorous) existence for these creatures, at least through Davis’s eyes. But when we read some of her other stories, we are reminded that other animals may experience a different momentum in their daily lives. In her story “Cockroaches in Autumn,” (from: The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis, Picador, 2009) the featured critter’s activities are marked by speed rather than stillness:

[. . .] when I empty the bag, a crowd of them scatter from the heel of rye bread, like rye seeds across the counter, like raisins. [. . .] he stops short in his headlong rush and tries a few other moves almost simultaneously, a bumper car jolting in place on the white drainboard.”

While I found The Cows to be a thoroughly satisfying read on its own, it was particularly enriching to meet Davis’s cockroaches, mice, cat, and dog along with her neighbors’ cattle. I recommend The Collected Stories as companion pieces to this chapbook.

Lydia Davis is a short story writer, novelist, and translator. She is the author of six collections of short stories, including Can’t and Won’t (2014) and The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis (2009); one novel, The End of the Story (1995); and a collection of nonfiction, Essays One (2019), which was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. Davis is best known for her very short, micro- or “flash” fiction; many of her stories are a single sentence or paragraph long. She has translated novels and works of philosophy from French, including Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary (2010) and Marcel Proust’s Swann’s Way (2003). Her honors and awards include fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation, as well as the Man Booker International Prize. She is a professor emerita at SUNY Albany.

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/lydia-davis

S.M. Tsai spent many years doing archival research and writing, then turned to 9-5 jobs for a new learning environment. Her poetry appears or is forthcoming in Ricepaper Magazine, Blue Unicorn, and the chapbook Bubbles and Droplets: 10 Poems of 2020. She lives in Toronto with her plants.

Risa Denenberg is the curator at The Poetry Cafe Online.