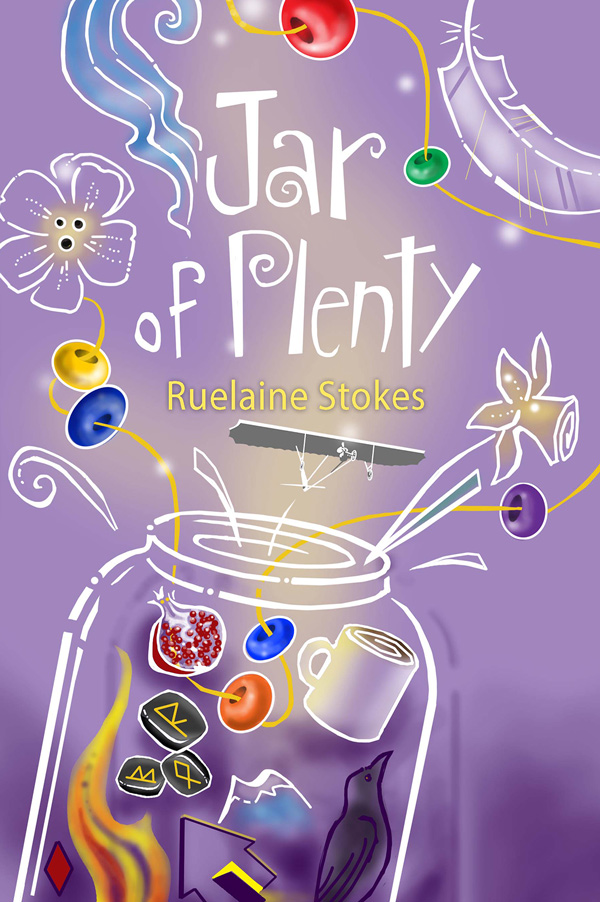

Jar of Plenty, by Ruelaine Stokes

Review by Cheryl Ceasar

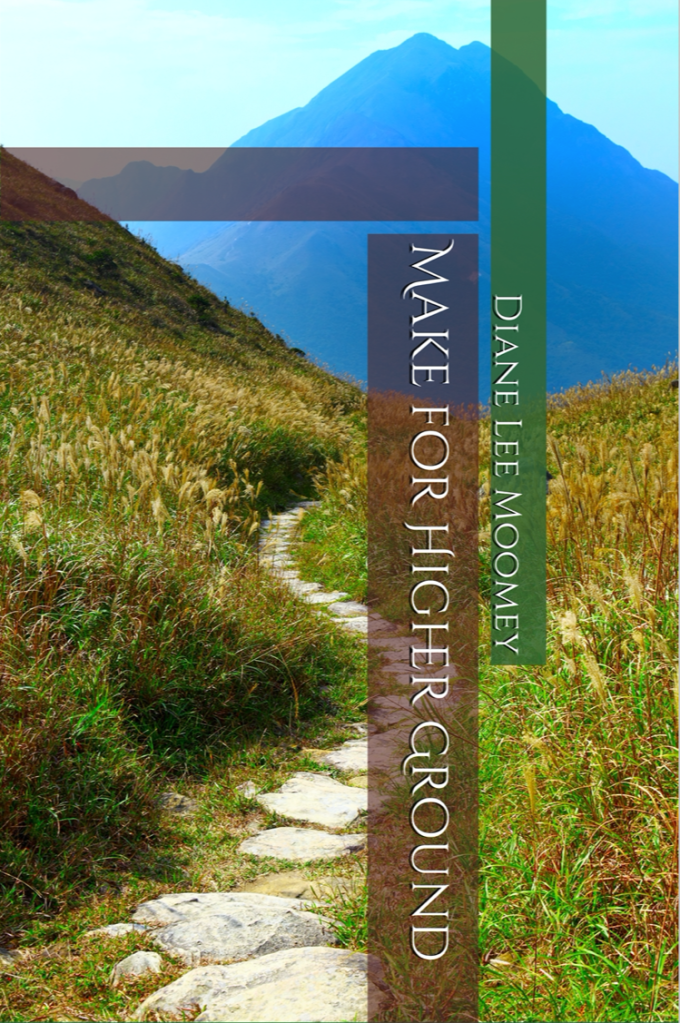

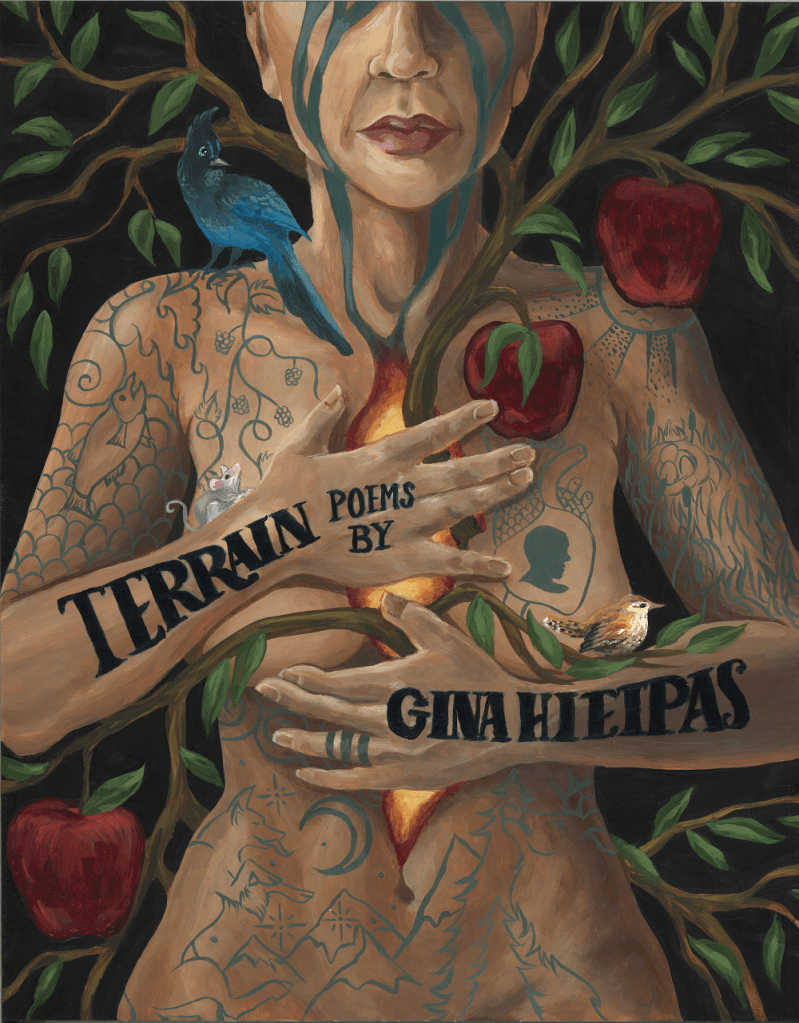

Cover Art by Barbara Hranlovich

As a child, I dreamed of exploding gift boxes. Not the tame ones you see online, those which simply unfold—although they can be quite lovely. I wanted to find a box that would spray its marvelous contents into the air like the novelty cans that unleash coiled snakes, but with no danger of a chipped front tooth or a poke in the eye. When I opened a manila envelope from my friend Ruelaine Stokes a few days before Christmas, I finally got my wish. The book Jar of Plenty is not only a gift, but a reminder of what a gift can mean.

Start with the cover art by Barbara Hranlovich. On an indigo-chakra background, a white-outlined jar is releasing beads, runic stones, flowers and feathers. An opened pomegranate discloses its secret rubies. A cup of coffee in a plain white mug flourishes its artisanal swirl of foam. A wise raven lifts its beak as flames flicker and steam rises. It recalls the childhood pleasure of plunging my hand into a cookie tin full of variegated buttons.

Open the book; the gifts continue to stream out. Ruelaine draws on her own gift, her talent, to fashion these small parcels of delight. Like a smiling hostess, she guides us through the rooms of her various names, arising from her deep self.

Rue: a street or a regret

Lynne: like a brook or small pool, from her father’s friend

Stokes: from her ancestors, as in the line, “Keep the fire burning,” from her poem, “The Story of a Name”

Alongside black-and-white photos, she introduces her family: The grandfather who fell like Icarus from the sky in “Sailing through Time”; the pretty mother who fled to Tijuana with the priest in “Hard Times for Free Spirits”; the Monster who “sits by the door” and tells the writer she was “never designed to fly” in “Monster”; and then, the writer herself, out the door and flying.

Ruelaine picks up the ordinary artifacts of our lives, one by one, to show their marvels. Here is a pomegranate with its seeds: “each translucent / each bearing the fate of the world,” in “I remember the far-off sky, blue and blazing.” Here are memories of the senses, vividly evoked in “Yellowstone”:

the low moan of the wind

the hungry grass

the gray stones

I think the gift she is sharing is this: the gift of attention. Attention to every small object, attention to our movements through the world. In “The Priest of Coffee,” the passing of the cup becomes a sacrament, reminding us that every sharing of food or drink is a potential communion.

As I read, another gift appears: a series of meditations, or perhaps a liturgy. Before the Communion comes the reading of the Lessons. “I am turning my sorrows into water,” she writes, with wisdom, in “Intangible Effects.” In “The Poet’s Prayer” is the artist’s petition to the universe: “let me cast these notes / into the wind.” And, the poem, “From the Book of Common Prayer,” grants absolution: “wash my heart and call me clean / the hard time is over.”

A real gift is a moment of connection, passed between outstretched hands. Ruelaine’s life so far has been gifted to poetry, and especially to the local poetry scene in Lansing, Michigan. For decades she has worked here as an “architect of reality”–her own phrase—building the structures, readings, and workshops that bring poets together for a moment of communion. What a joy to find a collection of such moments made tangible and lasting, an artifact of her life’s gift.

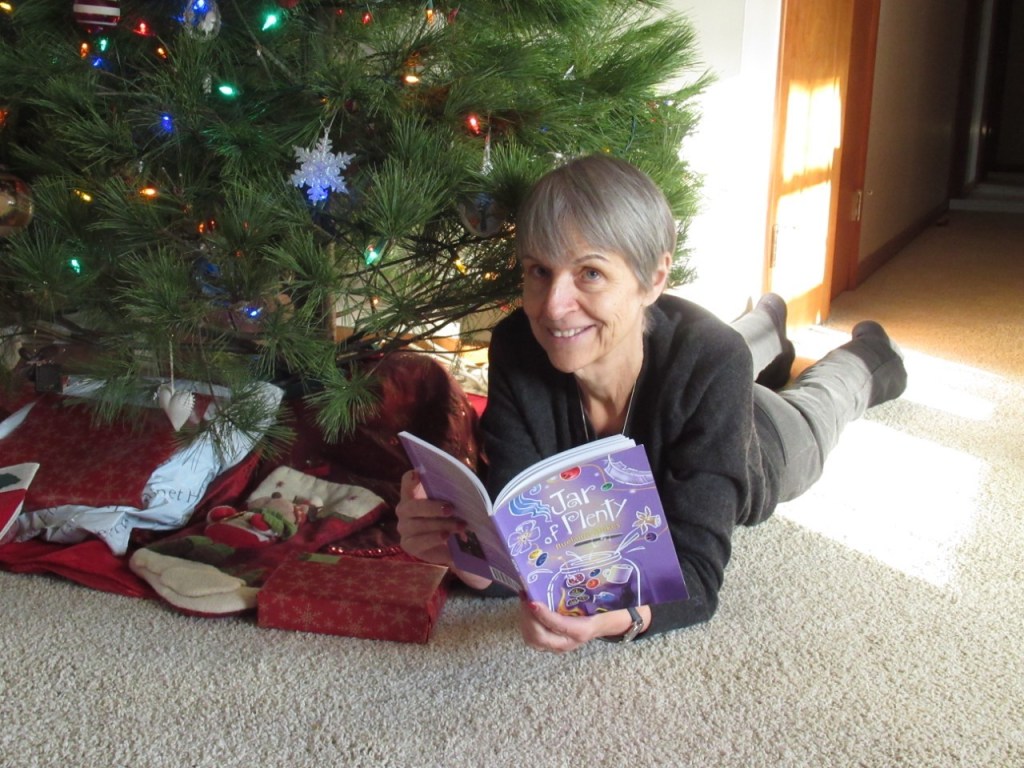

Ruelaine Stokes is a poet, spoken word artist, teacher and arts organizer based in Lansing, Michigan. She has a BA in English literature from Stanford University, an MA in English literature from Michigan State University, and an MA in Teaching from the School for International Training in Brattleboro, Vermont. She worked for many years teaching English as a Second Language at Michigan State University, Lansing Community College, and in community ESL programs. She has also taught classes in English literature, Poetry, Women’s History and Writing. For many years, she has organized poetry performances, readings, open mic events and workshops within Mid-Michigan. She is currently the president of the Lansing Poetry Club.

Title: Jar of Plenty

Author: Ruelaine Stokes

Published by Author, 2019 (Printing Services at Michigan State University Libraries)

pp. 74 $15

ISBN is 9780578339085

Cover Art: Barbara Hranlovich

Cheryl Caesar lived in Paris, Tuscany and Sligo for 25 years; she earned her doctorate in comparative literature at the Sorbonne. She teaches writing at Michigan State University. Some of her COVID-era poems appear in Rejoice Everyone! Reo Town Reading Anthology, and in The Social Gap Experiment, both available from Amazon. Her writing and artwork will appear soon in Words Across the Water, a joint anthology by the Lansing Poetry Club and the Poets’ Club of Chicago. With co-editor Ruelaine Stokes, she is gathering a volume of reminiscences of the Lansing poetry scene in the 70s and 80s.

Risa Denenberg is the curator at The Poetry Cafe.